Here’s a report on our day at the Women’s Centre in Dunkirk Refugee Camp. A huge thank you to everyone who donated to the GoFundMe campaign — we raised £1600 and every penny is already making a difference.

This thing started off because a friend of mine went to the refugee camps in France a few weeks back on a journalism assignment. We happened to meet for lunch the day after he returned and he told me about the Dunkirk Women’s Centre, which was doing incredible work creating a safe and welcoming space for the camp’s 150-strong group of women and their children. There had been recent reports of a problem with sexual violence in the camp, and there was an ongoing need for nappies for both adults and kids – so neither had to risk going out into the camp to find the toilets after dark.

Frankly this was all news to me. I had wrongly assumed that after the Calais Jungle closed that the system and situation just 30 miles from the UK had improved. That must be the case, I imagined, as I was no longer hearing anything about it on telly or in my FB feed. Which sounds silly when you say it out loud, but there it is.

Anyway, long story short, it seemed like a good idea to not use this as another opportunity to whinge about how fucked up the world is, and instead to actually try to do something about making things even just a little bit better. I spoke with my friend Laura and we figured we’d just hire a van, start a crowdfunder, buy a stack of nappies and drive over to deliver them. We originally planned to put some donations on someone else’s van, but since the Calais camp closed the supply runs from the UK seem to have dwindled and we couldn’t find a van making the trip, so we decided to drive one ourselves and see if we could fill it with the essentials.

Our friends and family were incredibly generous — the crowdfund target was originally set to £200 but over the weeks the donations rolled in and by the time we were due to drive off, the campaign had hit a massive £1600. Amazing. That’s 1300 size 6 nappies, over 500 adult women’s disposable pants, 50 tubs of sudocrem, 100 bottles of baby shampoo, 60 children’s beakers, 100 sponges, 10 bottles of washing up liquid, 1000s of baby wipes and 12 pre-loaded 3 data sim cards, as well as a bunch of clothes and pots and pans donated by some of the kind people in our apartment building. We hired a van, bought petrol and booked our Eurotunnel tickets, with a little money left over for a direct cash donation to the centre. We were ready to go.

Dropping off donations was really easy. It is literally a 3 hour drive from London to Dunkirk with a 30 minute snooze on the Eurotunnel. The Dunkirk camp is just 20km up the road from the Calais terminal, and the supply warehouse is about a 1 km outside of the actual camp, really close to a supermarket complex. It was simple case of driving in off the motorway. The warehouse is well manned and organised with drop off stations for clothes and kitchen equipment, as well as a dedicated room for supplies for the women’s centre.

As we began unloading the van we were met a couple of girls volunteering in Dunkirk from Gynecologie Sans Frontieres. They helped us bring everything inside, and thankfully seemed really pleased with the things we had brought. “Yes, we need this,” they kept saying, which frankly was a relief as while we had stuck pretty diligently to their ‘urgent needs’ list the centre had emailed me two weeks before, it seemed hard to know whether they would still need these things 2 weeks and many donations later. Size 6 nappies however are always in demand, they said, and we saw for ourselves that the supply room was stacked high with size 2 and 3 nappies for small babies (of which there is only one in the camp), compared to just a few packets for the size 6 toddlers, of which there are scores.

We asked the girls from GSF about whether it would be worth us visiting the women’s centre itself, to see how things were set up and if there was anything else we could do to help while we were here. In my emails and text messages with the volunteers at the centre they had asked if we would be visiting them, but even with their encouragement the idea was something we were a little hesitant about; we didn’t want to get there and find ourselves just awkwardly hanging around unable to do anything useful. The GSF girls however didn’t hesitate — ‘of course you should go,’ they said immediately. They gave us directions and a few minutes later we had parked up and wandered towards the security portacabin past four large police security vans. We signed in, and in we went.

Luckily, we noticed a small group of volunteers in high vis jackets close by. They told us they knew where the women’s centre was, and so we followed them along the main ‘road’ through the camp until we reached wooden structure painted with a sign advertising free women’s clothes. The women’s centre. After a few awkward moments at the door unsure of whether to enter, we were welcomed with warm smiles by two of the volunteers running the space, and invited inside.

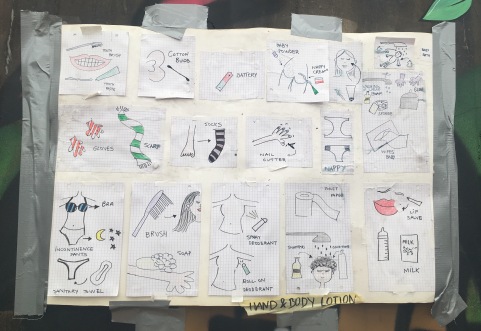

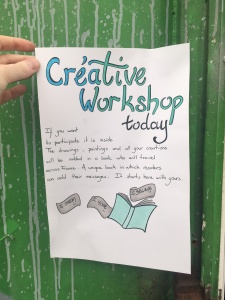

The centre couldn’t be more of a contrast to the space outside. Bright, colourful; decorated with bunting ribbons and fresh painted murals, a wood burning stove in the middle of the seating area to keep everyone warm. There are posters on the walls advertising creative workshops and baby weaning classes, and around 10-15 women and half a dozen toddlers are sat around knitting, painting nails, drinking tea. Men occasionally drop by with kids, and wait outside at the main door for them to be escorted to meet their mums inside. It really is a safe haven for the 100+ women here, operating in a very difficult environment, and is the only women’s centre still running in the camps in this region.

We are there about 5 mins before one of the senior volunteers walks over and asks which of us is most practical. I say Laura is: so now Laura is off with long-term (2 month) volunteer Liz to replace the locks on the women’s toilet doors so they’re more secure. Not such an easy job, as it turns out. The door frames need new holes drilled in them to make space for the lock bolts, and the only drill in the camp is quickly running out of battery. Over the next hour, Liz and Laura are trouble-shooting. Maybe they can find a battery. An adapter. Maybe a rock and a screw will do the job. Maybe they can fit blocks of wood to the doors and fit the locks on those, so the bolts slide across the back of the door frame and don’t need new holes drilling at all. But where can we find wood that’s sturdy enough? And screws? And a saw? They head off towards the phone charging station in search of tools.

Meanwhile, the centre’s longer term volunteers invite me to start organising the stock from the warehouse that has just been brought to the free shop next to the women’s centre, so I spend the next few hours sorting through bags of shower gels and shampoos, socks and scarves, stacking size six nappies on top of each other. There was no shampoo left this week, but now there is loads, so we refill the empty boxes from bags brought that morning from the place we had just visited with our donations. Occasionally women come to the door: one searching for a towel to dry her wet hair after a haircut in the centre, another whose baby is sick and needs more nappies. The shop is officially closed, but it seems urgent so we start sorting through boxes picking out the sized 5s.

After an hour or so I realize Laura had been gone for a while. I wander to the ladies toilet portacabin and find her with Liz amongst around 8 security guards and camp officials (none of whom we had seen at any other point in our day). I really wondered where they had suddenly come from. There is a mix of shouting and arguing and then some laughing, mostly in French. It seems they were not at all happy Liz and Laura had attempted to fix the doors locks by drilling into them, by themselves, as these toilets ‘belong to the mayor’s office’. This seems faintly ridiculous under the circumstances, and after some long deliberations and Liz’s French repetition of the words ‘the locks don’t work, the women are scared’, it seems like the logic of having women’s toilets that actually lock is not lost. Soon enough, one of the camp guards arrives with what appears to be the only large drill on the site and sets to completing the work Laura and Liz started.

There is clapping and cheering when he finishes the job. The crowd has grown and everyone is laughing, mixing languages and giggling at Liz for trying to fix the locks with a long screw and a rock. Everyone seems to be feeling pretty happy that a small solution to an important problem was found, even if it’s one that’s been there for weeks and no one in the official set up has addressed until Liz and Laura decided to take it on.

It’s 4pm suddenly, and we have to leave to get the Eurotunnel home. We wander around finding people we’ve met and worked with that afternoon, hugging and saying goodbyes, before slowly wandering back out of the camp. It’s a total cliché to say it but as we leave I don’t really feel intimidated any more. We know the terrain, we recognise some faces as we pass. One of the men shouts after us telling us to ‘smile’, and we realize he has a Brummy accent and wonder what on earth he is doing here.

We get to wander out easily, back into the van, onto the Eurotunnel, back to our London flat for dinner time and an order of take out food, which all just feels really weird. Meanwhile this temporary stretch of land to the south of the motorway near Dunkirk there is a barely bearable shelter for around 1500 people who have no other option, sleeping in rickety wooden huts, no electricity after 6pm, cold, damp, without locks on the toilets, unsure of what will happen to them next. According to local reports, the camp is likely to be cleared in the not too distant future. No idea what the plans are for it’s residents.

One thing that is without question however is that this sad state of stasis is made better by the tireless work of a few volunteers — like those at the women’s centre. Just normal people taking some time out of their lives to inject a sense of safety and warmth and colour into the bleakness, while making sure the women and children get the essentials they need.

We’re really pleased we got to help for a day, and really humbled by the donations of friends to this cause. We saw exactly where and to whom that money and those nappies are going, and trust us, it will make a difference. Thanks to everyone.

Finally, here’s a picture of a post-it on one of the walls at the centre. I liked it, and thought you might too.

If you’d like to support the centre or find out more about their work, you can visit their Facebook page, or just make a donation on their brand new website. You can share this story with your friends. And of course, you can always drive over and volunteer for a day or a week or two — you’re always welcome.

![FullSizeRender[3]](https://borderskipping.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/fullsizerender3.jpg?w=450&h=375)